Student Archaeologists Continue an Unlikely Partnership

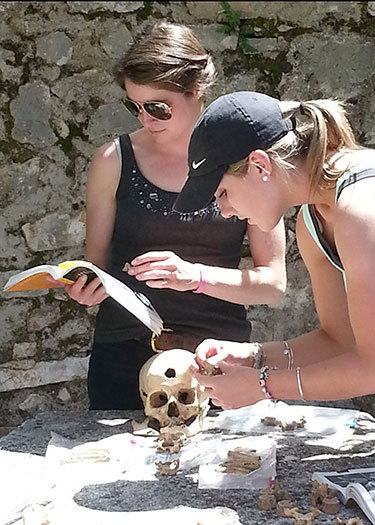

By David Chanatry (NCPR) (Source: New York Reporting Project at Utica College.) A group of college students from upstate New York spent three weeks studying bones at an ancient archaeological site in southern Albania. More and more American students are studying abroad, especially in shorter programs like this one. But according to the Institute of International Education, Albania is rarely their destination. But this group was just the most recent class to take part in an unlikely collaboration between Utica College and a national park in this little known part of the world. The shade of a palm tree is an unusual place for students from Utica College to take a class, but that’s where Tom Crist teaches his summer course in osteology, the study of bones. Standing at the head of a concrete picnic table recently, Crist carefully lifted a human skull—from a plastic Ziploc bag. “So you are meeting your first Butrint individual,” Crist told the students. “This is from burial 1250 from area 19. You can see some of the orbital bone is broken away here. That is post-mortem loss.”

|

|

|

Crist is a bones guy. He teaches forensic anthropology at Utica College, and right after graduation this year he brought a dozen students to do field work in Albania’s Butrint National Park. For the 11th year in a row, his students from Utica College and other schools from around the country studied under that palm tree. They were learning how to identify bones, and the markers of disease, skills that can be applied in law enforcement or working for medical examiners. But Crist said the course offers more than forensic technique. “We could offer a course like this anywhere, even at home,” he said. “The extra benefits of coming to a place like Butrint is the opportunity to visit unusual parts of the world, for most Americans, to having skeletal remains from hundreds or thousands of years of occupation.” Junior Katelin Briggs said that connection to place gives her the chills. “When we’re looking at the bones or we’re actually like trying to figure out like who were these people, how old were they, what’s their gender and stuff like that, these people walked right where we’re walking,” she said. |

|

And those people have quite the pedigree. Located on the shores of the Ionian Sea, Butrint was a crossroads of the ancient world. Ruins of a Greek amphitheater sit right next to a Roman forum, temples and baths; there’s a Medieval cathedral and baptistery; a Venetian tower and an Ottoman fort. The layers of history go back three thousand years. That struck a chord with Paul Ukena who just graduated from Utica. “What’s interesting about the park is really the scope of it, how much it’s changed over time, and your being the person there much later in history you become part of that history,” said Ukena. Working with bones that old can be tricky. Kaylan Campbell joined the group from Colorado State University. She spent hours washing and helping to catalog bones archaeologists recently excavated near the forum. “They’re very fragile when they’re wet so you want to make sure you’re getting the right amount of dirt and everything off, but not to break them because that is not good,” said Campbell. “Some of the smaller fragments, it was challenging.” There is more to this program than dead people: side trips to more modern cities and museums, and interacting with the living for three weeks. SUNY Oneonta student Jessica Scalise had never been on a plane before coming to Butrint. Now she’s become a cheerleader for foreign travel, “I feel like its something that’s so important to just open up your world, and see people who do things differently than you and understand other cultures and just really see what is outside your own little world.” Getting out of their comfort zones, Tom Crist notes, is something the ancients had to do too, “It’s remarkable to me to think of these people coming to this part of the world and making a community, a society for themselves here where nothing was before.” Much of the site remains unexplored woodland and floodplain. With more excavations potentially to come, the students from upstate New York should have plenty more skeletal remains to learn from.

Listen to this Story |

Back: Saranda, Albania